The British brought Indians into the lower levels of the civil service but never allowed any to fill positions of power. He shows the British destroying India shipbuilding and blocking an Indian iron and steel industry. Tharoor documents the British destruction of the Indian textile industry to allow imports of Manchester-made fabric into a captive Indian market. Of course, as Tharoor points out, Indians in vast numbers died for an Empire that otherwise oppressed them in a dozen 19th-century colonial wars in Africa and Asia and in two world wars, “which,” as Tharoor writes, “had nothing to do with India and everything to do with protecting or expanding British interests.” One might add, by similar depredations in China, Singapore, Hong Kong, West, and East Africa, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, although in the case of the latter three, mostly exploitation of human resources during war. Its depredations in India financed the British rise for 200 years.”

The reason was simple: India was governed for the benefit of Britain.

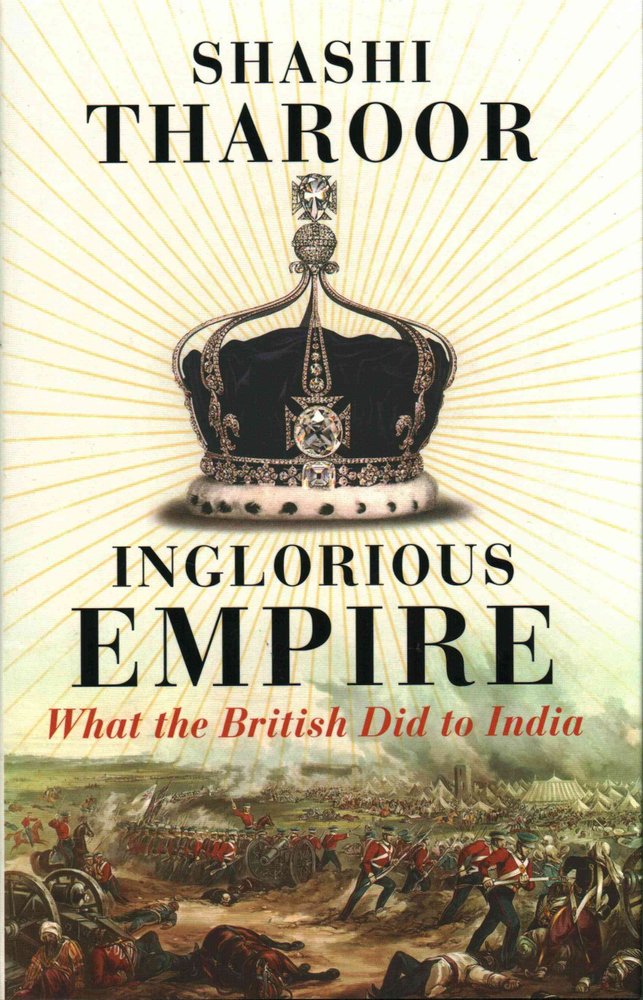

“By the time the British departed India, it had dropped to just over 3 percent. “(It was 27 percent in 1700 when the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb’s treasury raked in 100 million pounds in tax revenues alone). “At the beginning of the eighteenth century, as the British economic historian Angus Maddison has demonstrated, India’s share of the world economy was 23 percent, as large as all of Europe put together,” Tharoor writes. His Inglorious Empire (also published under the title An Era of Darkness) is an eight-chapter, 250-page indictment of the British for sucking the wealth and resources out of India for more than 200 years of plunder. “But in more complex situations, it cannot and, more to the point, does not work as well.” “Gandhiism is viable at its simplest and most profound in the service of a transcendental principle like independence from foreign rule,” Tharoor writes. He is even miffed at one of his idols, Mahatma Gandhi. He is angry at historian Niall Ferguson for suggesting that the British occupation benefitted India. He is angry at Rudyard Kipling for being a romantic imperialist and inventing “the white man’s burden. He is angry at Winston Churchill for being an obdurate imperialist. He is bitter at the British as he outlines their more than two centuries of exploiting Indian resources and people, then departing hastily in 1947 to permit a partition during which hundreds of thousands died.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)